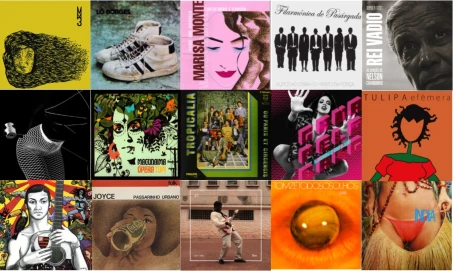

Quarantine, voluntary or otherwise, offers a time to find new adventures in confined spaces. I offered some suggestions on exploring Brazilian music through classic albums here, but this blog is mainly devoted to newer stuff, so of course I’m going to make suggestions there, too. Where the classic albums were pretty obvious, this list is more idiosyncratic because current music isn’t canonical (yet), plus I actually know it better than the classic stuff and feel freer to range off the beaten path. That I limited it to only three Clube da Encruza related albums is a testament to my willpower. So ten current albums in historical order (and, yes, I really should have a Sepultura album, but I don’t know them well enough to pick):

Suba, São Paulo Confessions (1999) – Mitar Subotic was Serbian ex-pat who became a producing phenom in Brazil where he merged his adopted homeland’s musics with international dance trends. Those dance music trends sound somewhat dated here on his final album, but it’s still an intoxicating mix of old and new, as well as a harbinger of the international community rediscovering Brazilian music this millennium. Tragically he died a few days after the release of this album when his studio caught fire and he tried to rescue recordings before they were destroyed. If you like try: Bebel Gilberto, Tanto Tempo; Smoke City, Flying Away, Céu, Céu.

Tribalistas, Tribalistas (2002)– The rare supergroup that works, Tribalistas brought together the talents of Marisa Monte, Carlinhos Brown and Arnaldo Antunes. As wonderful as the last two are, the real star is Monte, who might be the finest Brazilian musician since the country’s ’60s/’70s heyday. Light and playful in the best Brazilian tradition, strong melodies are swept along by mellifluous percussion that grounds music that threatens to float away. At the center is Monte’s clear, seductive voice oozing smarts and warmth. Tops is “Já Sei Namorar”, which is in the competition for the best song of the ’00s. As in worldwide, not just Brazil. If you like try: Tribalistas, Tribalistas (2017); Marisa Monte, Verde, Anil, Amarelo, Cor de Rosa e Carvão (called Rose and Charcoal in English-language markets), Marisa Monte, Barulhinho Bom.

DonaZica, Composição (2003) – Formed by Anelis Assumpção (daughter of Itamar), Iara Rennó (daughter of Carlos Rennó and Alzira Espíndola) and Andreia Dias (daughter of overly strict evangelical Christians), DonaZica was an all too brief blazing glory of Brazilian music. Their debut is a riot of pleasure, confidence and fun, with dense, ear-tickling arrangements and playful, tag-team vocals as they decorate samba with all kinds of modern touches. All three women went on to notable solo careers, while many of the instrumentalists—notably guitarist Gustavo Ruiz in his work with his sister Tulipa—made a mark, too. One of the best four or five Brazilian albums I’ve heard this millennium. If you like try: Iara Rennó, Macunaíma Ópera Tupi; Anelis Assumpção, Taurina.

Karol Conká, Batuk Freak (2013) – As with rock music, hip hop was not a natural graft onto Brazilian styles, but a culture as deeply musical as Brazil did figure out how to cannibalize it for domestic use. Frenetic and funky, Nave’s production provides an ideal environment for Conká’s charismatic rapping. His harsh samples and sounds create the kind of deep dive your ears can get lost in as hooks, bleeps and blaps are pushed to the point of annoyance without actually getting there. Yet the dazzling production never overwhelms Conká, who remains the star. If you like try: Lurdez da Luz, Gano Pelo Bang; Black Alien, O Ano do Macaco – Babylon by Gus, Vol. 1.

Elza Soares, A Mulher do Fim do Mundo (2015) – A famed MPB singer with a made-for-dramatization biography, Soares had basically been retired for a decade before the then-septuagenarian made this shocking, brilliant comeback album. Teaming with São Paulo’s Clube da Encruza collective (see the next two entries), she released this striking avant-samba album unlike anything in her more commercially friendly catalog. Combining punky metallic guitar with carnival rhythms run through a blender, the music abrades and cleanses, while Soares’ voice, its technical virtuosity worn down by age, gasps, yelps and groans with life. If you like try: Elza Soares, Deus é Mulher; Juçara Marçal, Encarnado.

Romulo Fróes, Rei Vadio: A Canções de Nelson Cavaquinho (2016) – Connecting past with present is how a tradition stays alive, and tribute albums are a key way Brazilian musicians both honor the past while not being trapped by it. But few of such albums both honor and reinvent with the chutzpah of this triumph. Fróes, as one of the leaders of the Clube da Encruza collective, had been revitalizing samba for more than a decade. Like his compatriots, he loved Brazil’s traditions, but knew the world had changed. No gentle, lounge-worthy performances for him. Samba was music of the poor, the dispossessed, the street. Samba was a means of transgression as surely as the odd sounds of free jazz or punk guitar distortions that he tinged his music with. Back-to-back Fróes’ versions with Cavaquinho’s and the genius of both shines through. Fróes doesn’t just cover them, but deconstructs and reworks to show their continued vitality. A monumental record, as daring and successful as anything I put on that classic album list. If you like try: Romulo Fróes, Barulho Feio; Romulo Fróes & César Lacerda, O Meu Nome É Qualquer Um; Rodrigo Campos, Bahia Fantástica.

Metá Metá, MM3 (2016) – Kiko Dinucci, Thiago França and Juçara Marçal, with crucial support from Marcelo Cabral and Sérgio Machado, work up some of the finest racket in Brazilian music. Dinucci’s punk-metal samba guitar, França’s wailing sax, Marçal’s moaning roar atop Cabral’s and Machado’s rumbling rhythms steamrolls the listener. Over three superb albums, a solid live set and a pretty damn good dance score, Metá Metá has carved out a path combining rock energy with samba and Afro-Brazilian styles that has little parallel (or at least successful parallel) in Brazilian music. Where so much manguebit was stiff and conservative, Metá Metá is fluid and dynamic. On their most adventurous album, Dinucci paints the background with waves of distorted riffs while França and Marçal hold center stage and the rhythm section propels everything along. If you like try: Metá Metá, Metá Metá; Metá Metá, Metal Metal; Kiko Dinucci, Cortes Curtos; Passo Torto, Thiago França.

Carne Doce, Tônus (2018) – Brazil has certainly figured out rock better than America figured out samba, but that doesn’t mean the country’s musical culture has produced much that rivals the anglophone world’s output. Much Brazilian rock that I’ve heard tends to fall into the competent more than the inspired, but Goiânia’s Carne Doce is a definite exception. Drawing upon classic rock’s chops approach, the band works up a ferocious if smartly subtle virtuosity that shows off their instrumental prowess without ignoring the songs. Indeed, over three albums, the songwriting just gets better as the chops are even more smartly deployed to get the tunes across. As they get quieter with each album, their music smolders more, and vocalist Salma Jô matures into a pretty ace singer. While sounding nothing like them, the band reminds me of classic Fleetwood Mac in their ability to mix instrumental dexterity with quality songwriting. If you like try: Carne Doce, Princesa.

Dona Onete, Flor da Lua (2018) – Upon retirement from an academic career, Onete pursued her first love—singing—that her first husband had forbidden her from taking up. A regular gig at a local club turned into a recording deal, in which the septuagenarian adapted regional carimbó styles (from Northern Brazil) by spicing up the normally staid lyrics with love and lust. This live set draws from her first two albums and lets her soak up the adoration of an enthusiastic crowd as a crack band livens up the already lively arrangements. She’s having a blast. You will, too. If you like, try: Feitiço Caboclo, Banzeiro.

Baco Exu do Blues, Bluesman (2018) – This Bahian rapper emerged seemingly from nowhere—he had been around a few years—to produce the titanic Esú only to follow it up a year later with this even better album. Baco is one of the few Brazilian artists where not knowing Portuguese really frustrates, because even with lousy browser translation, his brilliance shines through as he wrestles with black identity in a nation whose racist legacy rivals the United States. But even as the full impact of the words evade, the music, developed with a host of producers, gets across, and his volcanic flow—explosive and liquid—pours out emotion that can’t be trapped behind a language barrier. Drawing deeply on Brazilian musics, he fashions a hip hop that sounds of its place rather than an import from abroad. If you like try: Baco Exu do Blues, Esú; Baco Exu do Blues, Não tem Bacanal na Quarentena; Leo Gandelman ft. Baco Exu do Blues, Hip Hop Machine #6.