Truth be told, I only got into the game about two thirds of the way through the decade. Elza Soares’ A Mulher do Fim do Mundo and Fabiano do Nascimento’s Dança dos Tempos made a splash stateside in 2015-2016. Jason Gubbels’ review of Romulo Fróes’ Por Elas Sem Elas sent me down an algorithmed rabbit hole and turned my ears southward for the rest of the decade as I discovered a ferment in Brazilian music as potent as it was in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s. Some 500 reviews later—most of them from this decade—I don’t regret the ear time devoted there. I haven’t been as excited or broadly engaged in new music since probably the early ‘90s.

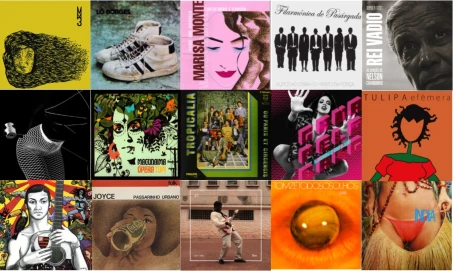

Below is the first of three summarizing projects I’ll do before decade’s end. These are the artists whose work has powered Brazilian music and tickled my ears.

1. Clube da Encruza – The plan was to include them separately. They—Metá Metá, Romulo Fróes, Rodrigo Campos—have done enough to earn their own to earn separate slots on this list. Heck, after practically flipping a coin to settle it, I had Fróes first and Metá Metá second on the draft. (Campos was sixth.) But as I wrote the entries, I kept cross referencing. Praising one meant including the others. Loose though this collective is—looser than the Mekons or P-Funk—it’s still a unit of some kind. Where would I put those Passo Torto collaborations if I separated the entries? How could I squeeze Marcelo Cabral’s critical background contributions in? Together and separately, Fróes, Campos, Cabral, Kiko Dinucci, Juçara Marçal, Thiago França and Sérgio Machado have made some of the finest music on the planet this decade. They’ve made the definitive Brazilian music of the decade in my opinion. The vast scope of their work—I count 52 (!) releases plus at least 27 significant contributions to recordings outside the collective—guarantees them a page in the history of Brazilian music in the ’10s, but the quality in the midst of that quantity is the truly astounding achievement. Contrary to some narratives, Brazilian music didn’t dry up after the mid-70s. But it’s also true that I haven’t heard an overall energy in Brazilian music this intoxicating since that time. It’s impossible to imagine summing up Brazil’s musical 2010s without giving the bulk of attention to the Clube.

From Fróes’ despairing arty sambas to Campos’ slick, twisted funky ones to Meta Meta’s explosive Afro-Brazilian punky ones, the collective drew inspiration from Oswald Andrade’s cultural cannibalism to make some of the most compelling Brazilian music since the tropicálistas drew from the same well of “antropofagia”. Their radicalized regurgitation of DIY’s arty anarchism within Brazilian musics looked backward and forward simultaneously as they demonstrated that samba and its cousins still had a place in a living musical culture. Neither retro nor cut off from the past, the Clube imagined how a century’s worth of recorded musical traditions could be reheard in a world where Elvis Presley and James Brown and the Velvet Underground and Ornette Coleman had reworked expectations. Not that the Clube sounded like any of those, but they lived in a Brazil, a world, where those American influences couldn’t be ignored. So they paid attention while remembering Nelson Cavaquinho, Cartola, Itamar Assumpção, Elza Soares and a host of their Brazilian predecessors. Soares is particularly instructive because their work with her has added a brilliant coda to an already legendary career. Soares wasn’t the only artist drawn into their orbit: Juliana Perdigão, Jards Macale, Lurdez da Luz, Criolo, Alessandra Leão, and others have made notable albums in league with at least some of the Clube members.

All of which was done while receiving little attention outside Brazil. Some English language coverage of Soares—notably Sounds and Colours—gave the Clube and samba sujo (dirty samba) its due, but elsewhere they were rarely acknowledged or noted as mere sidekicks for some of the artists they collaborated with. Even in Brazil they remained somewhat marginal figures outside of critical and artistic circles. Metá Metá’s monthly streams on Spotify edged past 80,000 as the decade ended, but Campos remained stuck around 20,000 while Fróes was down around 7,000. Yet pay attention to who follows them on Twitter and it’s a who’s who of Brazilian music and music journalism. Track down year-end lists from Brazilian music critics, and their albums keep appearing. To explain VU’s impact on popular music, Brian Eno claimed that while only 10,000 people bought The Velvet Underground and Nico, they all went on to form bands. Perhaps something similar is the case here.

Already the productions and guest appearances Clube members make across Brazilian music demonstrate their impact. Without their collaborations, Brazilian music would have sounded very different this decade. The Clube aren’t the only heroes of Brazilian music in the ‘10s, but they sit at the center of a scene that made São Paulo and its musicians as interesting as swinging London or ‘70s NYC punk. Which is why I can’t separate them into their distinct recording units in the end. Fróes, Campos, Dinucci, Marçal, França, Cabral, Machado, Metá Metá, Passo Torto, Sambanzo, A Espetacular Charanga do França, MarginalS, and all the other spinoffs are a collective movement and moment worth noting in a time when niche marketing and philosophical preferences have made monocultures and metanarratives passe. The Clube reminds us that scenes can bind together and create futures for cultures even in an age when capitalism’s radical individualism pushes us to be islands of consumption unto ourselves. No contemporary music I heard this decade anywhere compelled me to dig deeper. In a way, this blog is a love letter to the Clube and the musical culture it’s inspired this decade. So I guess this entry and their ranking in this list is just my way of saying thanks for all the music.

Five fab tracks: Metá Metá, “Logun”; Romulo Fróes, “Barulho Feio”; Rodrigo Campos, “Funatsu”; Passo Torto, “A Música da Mulher Morta”; Juçara Marçal, “Damião”.

2. Baco Exu do Blues – Baco didn’t come out of nowhere in 2017. He’d been around for a few years, and showed some promise. But the startling brilliance of Esú, followed a year later by the even better Bluesman, has made the Bahian rapper’s career rise seem meteoric. And all the praise is earned. With a dense rapping style that favors explosive emotion over verbal technique, he addresses racism and black experience in Brazil with a directness and insight that inspires and unsettles. He finds producers able to express both his blackness and his Brazilianness. His pace is breathtaking: nearly an album a year for three years plus half a dozen or so non-album singles. He’s said he wants to be Brazil’s Kanye West, but he should aim higher. If he keeps this up level of quality and insight up we’re talking Brazil’s Public Enemy.

Fab five tracks: “Capitães de Areia”, “Imortais e Fatais”, “Banho do Sol”, “Girassóis de Van Gogh”, “Kanye West da Bahia”

3. Elza Soares – She was already a legend. Her long career and compelling biography lifted her to the top ranks of Brazil’s popular singers. By the ‘10s she’d been in semi-retirement for several years. Then, she sang a song on Cacá Machado’s 2013 album Eslavosamba, which celebrated the burgeoning São Paulo scene. Next thing you know she’s working with the Clube da Encruza on two startling, avant-garde samba albums that sounded like nothing she’d ever done. A Mulher do Fim do Mundo (The Woman at the End of the World), is probably the most internationally acclaimed Brazilian album of the decade. After a solid followup, Deus é Mulher, with the Clube, she showed she was still in charge of her career, broke with those musicians and released a funk album this year that included a collaboration with BaianaSystem. While Soares’ voice is shot, her charisma and smarts remain intact even as she turned 80 in 2017. Compare her three albums this decade and you can hear how she adapts to the style she is singing and imprints her persona on the music to make it her own. She’s already planning another album for 2020.

Fab five tracks: Cacá Machado, “Sim”; Elza Soares, “Benedita”; Metá Metá, “Okuta Yangi No. 2”; Elza Soares, “Banho”; Elza Soares, “Libertação”

4. Carne Doce – Goiânia’s Carne Doce was Brazil’s best straight rock band of the ‘10s. Not that they rocked out that much. Bassist Anderson Maia and drummer Richardo Machado were a rhythm section capable of laying back while remaining intense. Guitarists Macloys Aquino and João Victor Santana showed off fluid chops while rarely one-upping the songs. And while singer Salma Jô’s voice might be an acquired taste, her charisma is indisputable. Over three albums they honed their songwriting skills and while developing the kind of deep, rewarding instrumental interplay rock bands did in the ‘70s before the cult of musical technique ruined the fun. Smart. Sexy. Songful. Not a bad combination.

Five fab tracks: “Fruta Elétrica”, “Benzin”, “Princesa”, “Açaí”, “Nova Nova”

5. Daniel Ganjaman – Producer/musician Ganjaman (nee Daniel Sanchez Takara) has been behind much of the best music of the decade. Ganjaman co-founded the producer’s collective Instituto in the ‘00s before going on to establish his own career as a leading producer in Brazilian music. More importantly, he hosted the famous Seleta Coletiva music party at Studio SP. The parties began in 2006, but by 2009-10 they had grown into a massive interaction of Paulista artists that juiced collaborations that played out across dozens of records over this decade. Without those parties, SP’s 2010s would have been very different and less fertile. Ganjaman’s production career continued strongly, too. Two of his more notable jobs were producing all of Criolo’s albums of the ‘10s (with the Clube da Encruza’s Marcelo Cabral) and BaianaSystem’s two hit albums. He also guided the posthumous completion of a number of slain rapper Sabotage’s unfinished tracks on the acclaimed self-titled album.

Five fab tracks: Criolo, “Subirusdoistiozin”; Criolo, “Casa de Paelão”; Sabotage, “Respeito É Lei”; BaianaSystem, “Jah Jah Revolta, Pt. 2”; BaianaSystem, “CertoPeloCertoh”

6. Tulipa Ruiz – Her father was a member of Itamar Assumpção’s seminal backing band Isca de Polícia. Her brother was in the short-lived ’00s dynamo DonaZica. But in the ‘10s Ruiz emerged from a career of background work to establish herself as one of the top Brazilian singers of the decade. Teaming with her brother, she moved effortlessly from indie pop to Brazilian rock to dance music to samba, with each move extending her reach and deepening her art as good albums got better as the decade went on. Besides her own stuff, she appeared upon dozens of albums in support roles, prized by her fellow artists for her distinctive singing, most notably a squiggle swoop that squeezes out a high register, attention grabbing whoop at the end. Comfortable singing straight or adding a dash of zaniness to electrify the moment (she has to have some treasured B-52 albums stashed away), Ruiz never settled for rehash. Even when, on Tu, she reworked previous numbers, the do-overs were distinctive and often improvements upon tunes that were strong in the first place.

Five fab tracks: “Só Sei Dançar Com Você”; “Like This”; “Expirou”; “Pedrinho” (2018 version), “Elixir”

7. Dona Onete – Onete’s love of music translated initially into an academic career due in no small part to an unsupportive first husband who quashed her performing dreams, but upon retirement the septuagenarian (now octogenarian) began singing in local haunts, which ended up leading to the recording career she’d wanted as a young woman. Working on a variation of the northern carimbó style that emphasized romance and passion over traditional subjects in the genre, she established herself as a performer whose charisma and fun blew past any limitations presented by her aged voice. Even better, she had more than one album in her. Her sophomore release expanded her stylistic grasp and toughened her grooves. She followed that up with a live album that is her gift to history and dropped a solid third album this year. Love, sex and good music aren’t just for the kids.

Five fab tracks: “Jamburana”, “Banzeiro”, “Queimoso e Tremoso”, “Propesta Indecente (Live)”, “Tambor do Norte”

8. Tom Zé – Rising from decades of obscurity in the ‘90s thanks to David Byrne’s patronage, Zé went on to be arguably the dominant Brazilian artist of the ‘90s and ‘00s, and although he’s slowed slightly as he entered his 70s and now 80s, he still had a strong decade leading with two more winning additions (Tropicália Lixo Lógico and Vira Lata Na Via Láctea) to his classic catalog before closing it out with a couple of minor, but still enticing efforts. His collaborations with younger musicians and still edgy music showed that this isolated oddball made the future of Brazilian music in the ’70s even if no one knew it at the time. You figure he can’t have much left in the tank, but considering he’s topped in this list by two more octogenarians, you wonder what they have in the water down there in Brazil.

Five fab tracks: “O Motorbói e Maria Clara”, “Aviso aos Passageiros”, “Banca de Jornal”, “Guga na Lavagem”; “Sexo”

9. BaianaSystem – The trio of Russo Passapusso, Roberto Barreto and Marcelo Seco plus whatever friends or collaborators decide to join them in the studio or onstage, emerged as dynamic heirs to Jorge Ben’s pioneering samba-funk. Their music looked to Africa, back to Brazil and then out to the African musica diaspora. Their politics excoriated right wingers while giving hope for everyone else. They teamed with Elza Soares for a great single in 2019. And reports say they’re one of the best live acts in Brazil. Their two albums this decade, plus a strong Passapusso solo effort, may not add up to much music quantitywise, but the quality is there. Maybe they’ll write a Brazilian “Stand Down Margaret” for Bolsonaro to start the next decade off right.

Five fab tracks: “Lucro (Descomprimindo)”, “Playsom”, “Barravenida, Pt. 2”, “Água”, “Sulamericano”

10. Juliana Perdigao – Beginning the decade as a member of Graveola, singer/clarinetist Juliana Perdigao participated in their solid sophomore album before breaking off into her solo career. Fusing Beatlesesque art-pop sensibilities with a love of her national musics, she proved both an adept cover artist—stealing songs from Romulo Fróes and Tulipa Ruiz—as well as a good songwriter. Her first album tended proggy, in a good way, but by the end of the decade she was writing tight, off-kilter songs that bent instruments to arrangements while still having the musical flourishes that keep the art in her pop.

Five fab tracks: “Recomeçaria”, “Céu Vermelho”, “Ó”, “Pierrô Lunático”, “Felino”

11. Criolo – Following an undistinguished debut album late last decade, Sao Paulo’s Criolo emerged as one of his nation’s most important rappers of the ‘10s. His 2011 release Nó Na Orelha, where he found decade-long partners with producers Daniel Ganjaman and Marcelo Cabral, is considered by many a landmark in Brazilian hip hop. Throughout the ‘00s Brazil’s hip hop scenes had shown more signs of moving past recycled North American funk beats toward a more distinctly national sound, so while Criolo may not have been the first to push the music in new directions, his ambition—embracing Africa, Jamaica, Latin America and Brazil—helped popularize new sounds in national hip hop. He deepened that sound on the follow-up, Convoque Seu Buda, and tied in more strongly to São Paulo’s vibrant scene before moving to an excellent straight samba album by the decade’s end.

Five fab tracks: “Sucrilhos”, “Pegue pra Ela”, “Fio de Prumo (Padê Onã)”, “Chuva Ácida”; “Dilúvio de Solidão”